(I’m not sure how I encountered this. Some sort of internet spelunking but who-knows-where.)

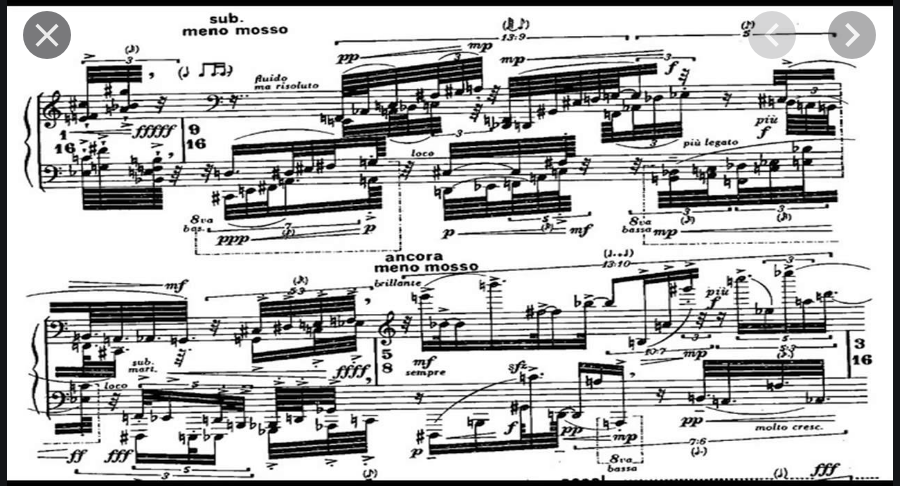

New Complexity is a composition style that originated in the 80s, consisting of inconceivably difficult music with beautifully difficult scores. Upon first listening, I felt that it was just a rehash of mid-century serial technique, at least in expressiveness. I fell into the “I’m smart enough to understand this immediately” trap of the moderately informed. It is instead yet something different and contains more performance/conceptual art aspects that put the responsibility of process on the performer as a way to manifest the ideas in the score. It may be a pendulum swing from what has been called the “downtown” style of minimalism that appeared in the late 60s/early 70s, which was itself a pendulum swing away from the atonality of decades prior. No style completely disappears, but I am happy to see a rhythmically- and harmonically-difficult style return.

I.

An excellent intro to New Complexity is Tom Service‘s article in The Guardian A guide to Brian Ferneyhough’s music, from 2012. He makes what was for me a revelatory observation:

[T]he desire to put all that information on the page is really the start of a dialogue, with the possibilities of what the performer is going to do with the piece and with what the listeners will hear. Even more fundamentally, the notation is a sort of scratching at the surface of what the actual musical work … might be.

This revealed and addressed the analytical conflict I was having with the style and suggested that, with New Complexity pieces, performers are not part of a contract of accuracy but rather a conduit of ideas. The complexity of the Second Viennese School was precise and the performances were–though not without nuance–following rigorous blueprints. These two styles are not different in aspect from the written notes of a Beethoven or a Rachmaninoff, but with the extreme complexity of New Complexity it needs to be said that there is still the requirement for a mediation between the score and the audience.

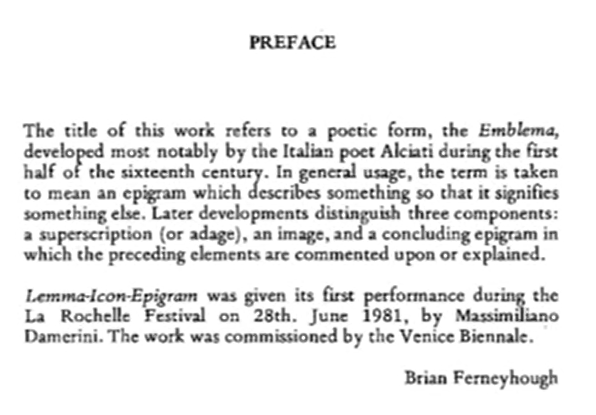

The proponents dislike the moniker, but what pigeon-holed artist actually likes their categorization (Baroque is not exactly a compliment)? I’ve so far listened to some pieces from the composers whose names I was somewhat-but-not-fully familiar with: Brian Ferneyhough (Lemma Icon Epigram, String Quartet No. 2, and Time and Motion Study II) and Michael Finnissy (English Country-Tunes and Snowdrift). Re-listenings are–it really goes without saying–required.

One of the few live performances I could find was of Nika Shirocorad performing Finnissy’s English Country-Tunes. It’s a fierce piece but the physicality of the performance is like watching an athlete. Yes it’s difficult, but there’s a beauty in watching the difficult be overcome or at least succumbed to. (Disclaimer: in YouTube comments for another video where she’s playing Chopin, a commenter lives up to the erudite reputation of YouTube commenters by saying “Far better than her interpretation on English Country-tunes”. Elsewhere, a Reddit commenter in a thread about the same piece notes that in her performance “she breezes through the first page in 5 seconds … not actually following the score closely”. I haven’t compared the score and her performance so take-from-that-what-you-will.)

After listening to several New Complexity pieces, I will admit that it can induce a bit of anguish in me. My first memory of astringent modern music is from when I was maybe 5 or 6 watching a sci-fi movie or somesuch–not sure I understood genre at that age–and there was a scene where a character runs across a concrete expanse and enters a metal-doored, cinder block hut containing some broadcast/electrical equipment. Spare. The actually scene may be nothing like that, but memory is memory. The soundtrack was some atonal string quartet (even though there’s no way I could have recognized “atonality” at the time). Finally encountering atonal music in HS must have triggered that memory of black-and-white bleakness, prompting an: “oh yeah, this is like that weird music I heard in that movie when I was a kid!” (Looking at the catalog of New World Records’ releases that I recognize I’d checked out from the town library, I see it could have been Henry Cowell‘s Quartet Euphometric or Gunther Schuller‘s String Quartet No. 2.) New Complexity is particularly good at evoking flashbacks to that weird memory maybe because there so much surprising beauty in there also.

II. Electric Chair Music

Time and Motion Study II bu Brian Ferneyhough. He considered sub-titling it Electric Chair Music but decided against such a material (?) choice that would suggest too much to the listener.

Time and Motion Study II (1973-76) – Essay on the work by the composer. Peters Edition Limited.

In the first instance this work is concerned with memory, with the manner in which memory sieves, colours and reorders that which is registered by the senses. A second level concerns itself with the construction of a model designed to demonstrate the fact that memory is discontinuous: something having a decided effect on perception, on the one hand in the form of ever-increasing “interference” in development, on the other as a necessary precondition for the historical consolidation of the individual.

…

[The work is transformed into] the conception of the self suspended in every moment between decay and consolidation.

…

[At the end] the performer is condemned to continue to the bitter end in the certain knowledge that all recorded tapes – his “memory” – are being silently erased behind his back.

Neil Heyde (cello) Paul Archbold (electronics)

Responding to the ‘heroic’ avant-garde of the 1970s – From Neil Heyde’s web site. Contains the documentary above and a video of the full performance.

Ferneyhough: “Obviously the term ‘time and motion study’ relates to the concept of efficiency in the industrial factory environment. How long it takes to make a certain object [and] what that object then costs the manufacturer so that he can make a profit from it selling it to somebody else.”

No program notes because it impedes the listener’s discovery of the work.

Plays with delays as counterpoint by the cellist against his prior performing self, mis-remembered, altering the present. History returns. Position of speakers.

Ferneyhough: “We don’t want to say do this do that what were really interested in doing is suggesting to people it might be interesting to investigate this particular area of what this notation is doing.”

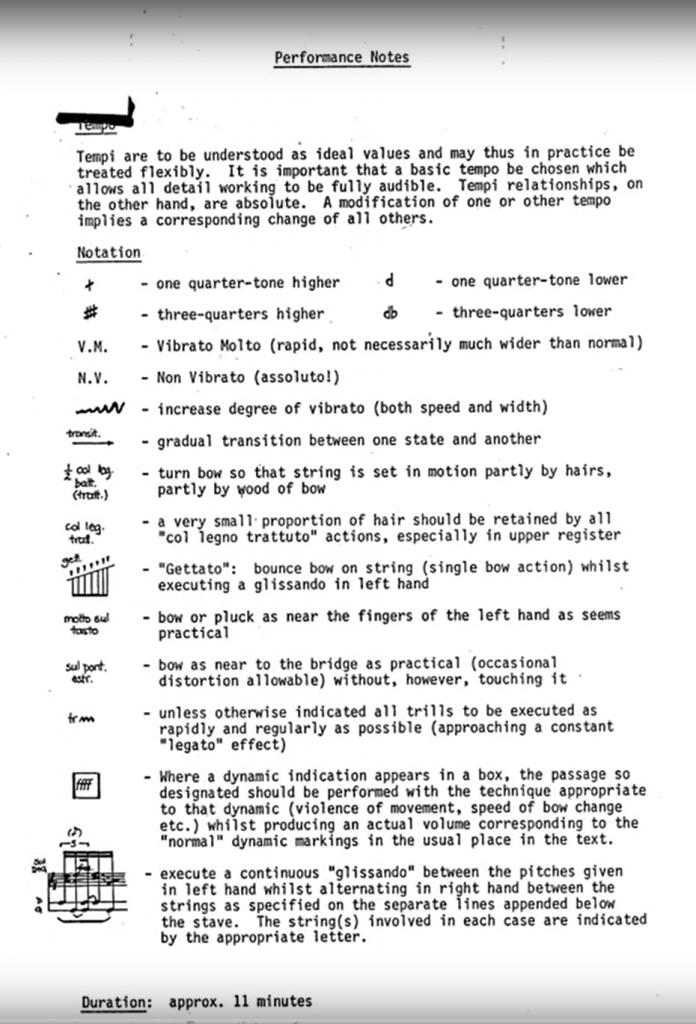

Playing style suggestions taken from different parts of the score:

exhibitionistic, but fastidious

sudden extremes of stillness and mobility, like certain reptiles and insects (i.e. praying mantis…)

schizophrenic: L.H. hysterical. R.H. as though sleepwalking.

with the utmost imaginable degree of violence

Score notes for the performer that will never be communicated to the audience. My piano teacher suggested writing lyrics for melodies or to mark down a metaphor for a musical phrase in order to create personal cues for the internal experiences I should have while performing.

III. Videos. Scores.

IV.

The question for me is always: can I adopt any aspects of this style in my own writing?