I’m very metrics-oriented: how long have I worked on a piece? How much music has been written? I read of writers feeling in the-same-or-similar way regarding how many pages they write in a day (it’s always very few). It’s been four months and I’m at 15 minutes of music. I don’t think that means anything.

At this point, I’m not sure that the turntable can hold up as a solo or chamber instrument. That’s a self-canceling suggestion since any instrument can be a member of an ensemble, but I’m trying to balance my fascination for the instrument against the actual experience. So more than self-canceling it’s self-reflective. Half full?

I just finished the 3rd movement, Barcarolle I/II, but still have maybe a week of cleanup. Late in the work I had a key revelation about Dorico’s functionality: I learned how to segregate dynamics between the upper and lower staffs of the piano part. This is a Very Basic Thing that, for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out originally and I would get wildly inconsistent results: sometimes working, sometimes not. I’m only getting intermittent inconsistent results now so… yay? It’s really not that difficult and I should have been shocked if they couldn’t do that–and was shocked–but it, as usual, was mostly user error. Cleaning up the mis-notated sections is going to be tedious (again: 15 minutes of music).

Pain is knowledge rushing in to fill a gap. When you stub your toe on the foot of the bed, that was a gap in knowledge. And the pain is a lot of information really quick. That’s what pain is.

–Jerry Seinfeld

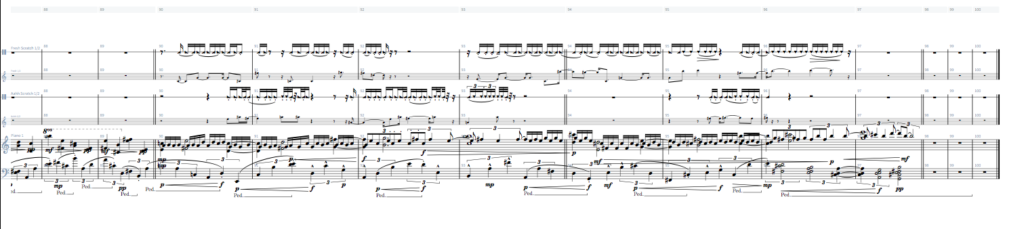

Using a script version of my simplified turntable notation system, I’ve gotten comfortable with writing melodies away from the actual Scratch Machine samples. The process has become: finish the piano accompaniment in part or whole by phrases, notate the turntable phrase on paper, choose the group of Scratch Machine pitches/samples that match the scratches I need for the notated phrases, flesh out my notated “melodies” in Dorico using fragments of the samples contained in the pitches. I rarely use the full sample (I’d commented on that before) and so those fragments are usually just the first 1-2 seconds of scratching. When similar motions are needed–say a simple scribble or baby scratch–there are many different samples that use the same technique but that are distinct in timbre. This is apparent in the top staff system (the “fresh” sample) of the image above, with the 2nd system (“ahhh”) adding punctuated color.

(Minor unrelated observation: the forward/backward scratch is equivalent to the up/down bow for bowed stringed instruments or the similar motion for strummed instruments.)

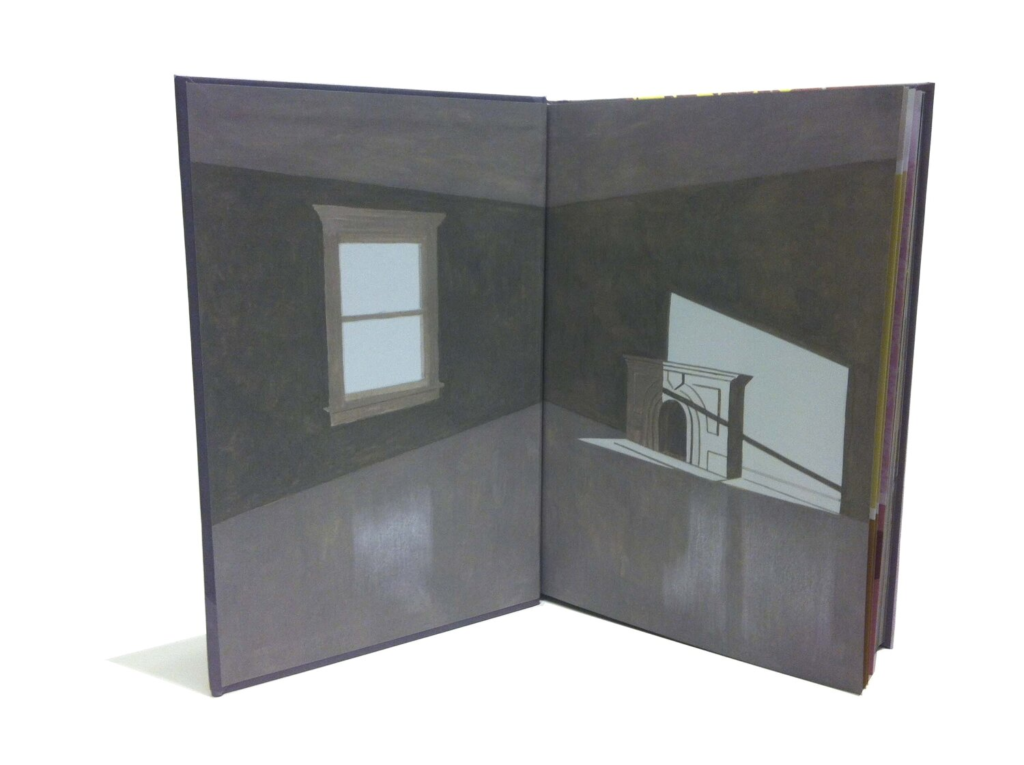

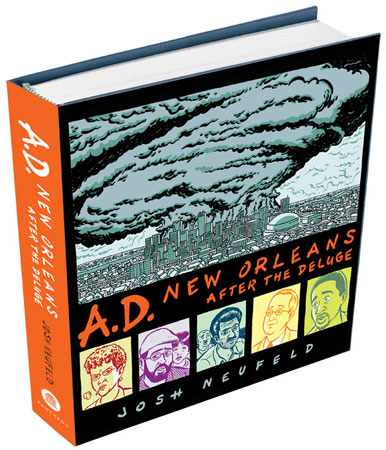

I somehow ended up following several people associated with City, University of London on my Twitter music account (@sstradermusic); not sure how, but likely from following Dr. Ian Pace (who I learn of when I was researching for A week of “The History of Photography in Sound”). Around a month and a half ago a post about a talk on how climate change can manifest a new narrative framework in graphic novels appeared in my feed: Apocalypse Yesterday: The Graphic Novel in the Anthropocene. It was hosted by Dr. Dominic Davies and presented to coincide with COP26 (the woefully under/un-reported conference going on at the time). Discussed were Richard McGuire’s Here and Josh Neufeld’s A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge–which unfortunately was cut short for time. Both unique narrative takes.

(To-be-read: Dr. Davies’ 2017 essay Comics and Graphic Narratives: A Global Cultural Commons

In the chat window during the talk, attendees posted minor comments or questions and one of them compared the narrative structure in Here to structural hearing in music. My ears perked up.

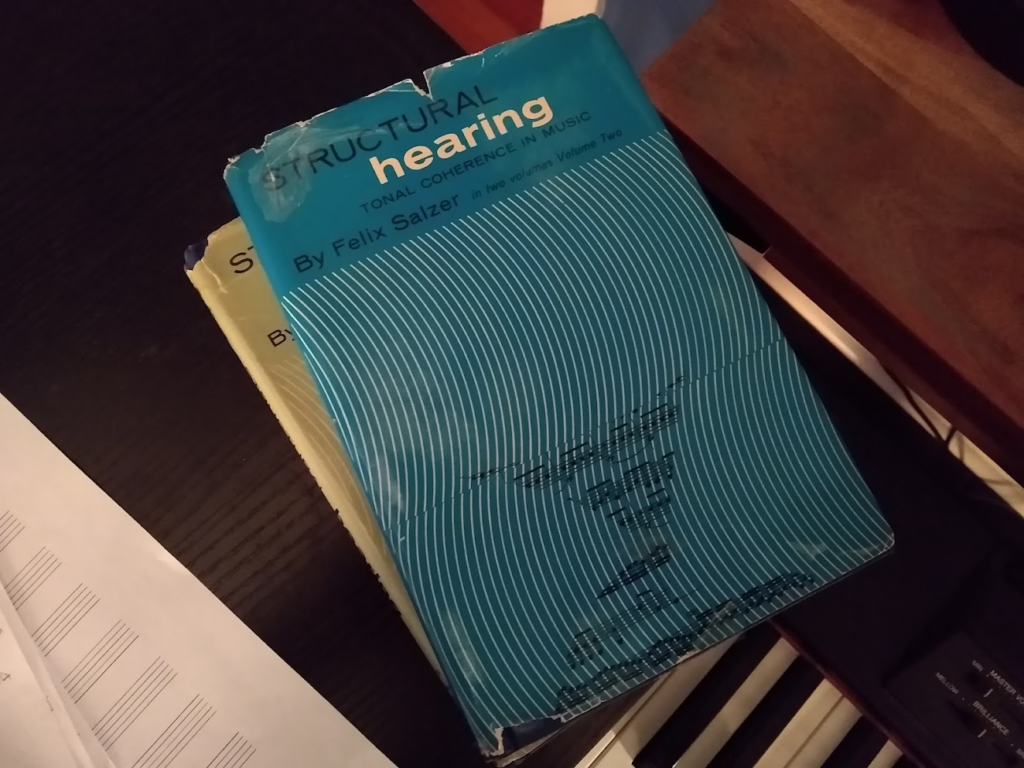

And that’s what’s good about virtual conferences: yes, you can more easily be distracted down rabbit holes but you can also dig up useful to-be-read-later articles and references. Which brings up a counter “but” since what I was researching was completely-ish unrelated to the talk at hand. Still, a good distraction. And that’s how I came across Felix Salzer’s two volume Structural Hearing.

Felix Salzer was a student of Schenker–he of the controversial-yet-compelling Schenkerian analysis. I had heard of that methodology originally in theory class, and that only in passing discussions but never as a class lesson. I knew of it but didn’t know it. I’ve been jonesing for a new book of music essays or theory, one that gets down to the metal and is more academic than philosophical. Much like the Pierre Boulez book and the pilfered PDF of Ferneyhaugh’s book, this will likely be a slow, piecemeal read.

But it’s what I needed.

(Somewhat related: I struggled to find good hardcover editions of Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (which contains the musical examples referenced in Vol. 1). I found only one site that had both in good condition but it was lost in the mail. Next I found an equally nice set on eBay which I bid on and was sniped in the last 20 minutes. I really thought I was safe with such an unusual textbook. Finally achieved the above.)