So far writing for turntables feels most similar to writing for tuned percussion. There’s also a sense that it’s somewhere between an acoustic and an electronic instrument. Though what I’m working with (samples) are more on the electronic side, I’m writing for an instrument that produces sound via physical movement and instrument vibration as opposed to spliced tapes or synthesized sounds initiated by, crudely stated but with no pejorative intent, a button push. There is a spectrum of physicality with electronic music, and there is a spectrum of electronic music as it moves further away from a human body initiating the sound. Although this is the first electronic-adjacent music I’ve worked with, it’s been an experience more familiar than expected because of the turntable’s percussive provenance.

The Hornbostel-Sachs classification codifies the different mechanisms that all instruments use to create sound and specifies five high-level categories of instruments: idiophones (the instrument itself vibrates, e.g. a xylophone or gong), membranophones (primarily drums), chordophones (stringed instruments), aerophones (brass and woodwinds), and electrophones (sounds created via electricity). I use “acoustic” here as a catch-all for the non-electrophone categories. I consider a turntable to be a composite instrument: the turntable needle vibrates (and can be heard without any electronic amplification) then is amplified and sometimes modified electronically. It can also be categorized using the term electroacoustic.

The samples I use from the the UVI Scratch Machine library are detached, being samples, from the original instrument but the principle is the same.

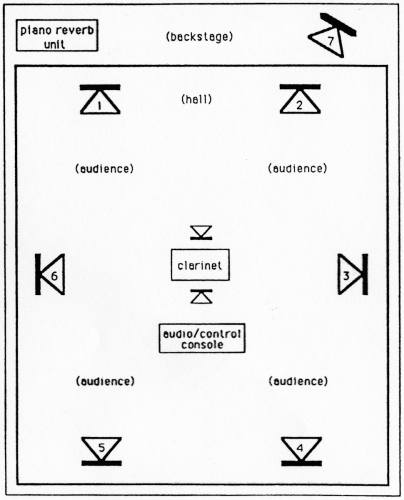

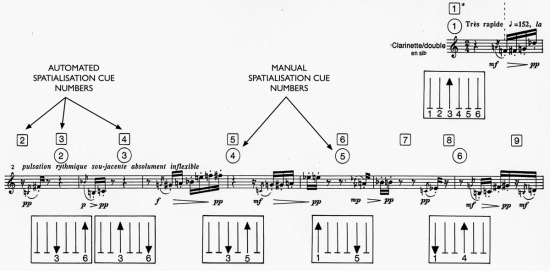

Boulez’s Dialogue de l’ombre double is written for a soloist plus pre-recorded tapes of music performed by the same soloist and so, to a degree, the composition is various combinations of duets. A live performance is intended to be in the round with the different recorded parts broadcast from speakers arrayed behind the audience. The article Analyse de Dialogue de l’ombre double de Pierre Boulez on IRCAM‘s website provides stage layout diagrams taken from Boulez’s score.

The score includes notation for how each recorded “performer” should enter and exit, along with spare electronic effects (reverb). I’m not sure if the fader notation he uses is some industry standard or of his own creation, but it works very well.

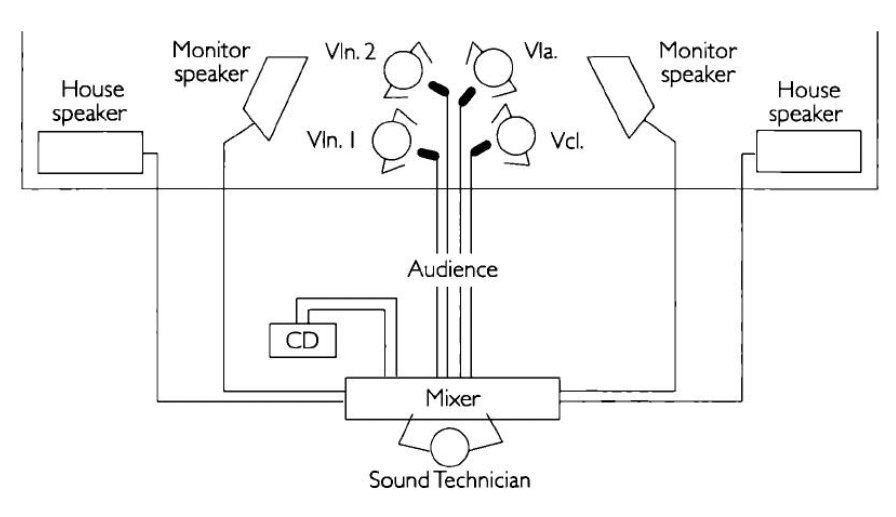

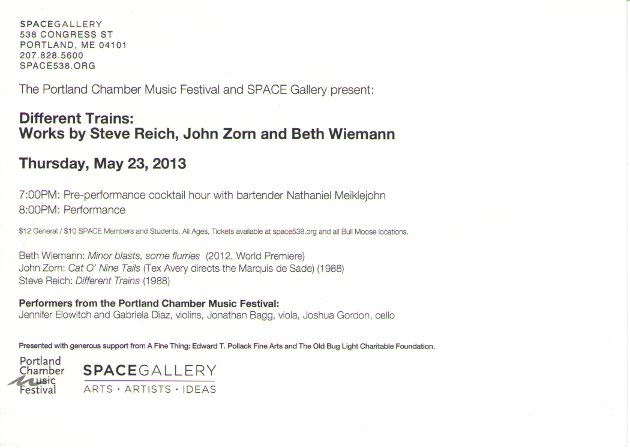

Reich’s Different Trains is written for four string quartets, fragments of recorded interviews, and recordings of train whistles. The string quartets consist of one quartet playing against a recording of three others. (The recorded interviews, train whistles, and three string quartets are provided on a CD with the score.) The recorded parts lean into the “push a button” type of electronics, but they all are acoustically generated. (As an aside: I recommend to use as a reference sheet Neil Haydock’s quantifying analysis of each recorded voice fragment used in the composition.)

Based on the performance notes, the sound technician is a key component to any performance, with nearly all of the instructions directed at them. This harkens back to the Boulez notes. One could note here that while the string players are required to perform almost 30 minutes of rigorous, nearly mechanical exercises, the technician is given the greater share of responsibility and conductor-like creativity.

Re-listening to the piece, I realize how much the sound sits in between a string quartet and a string chamber orchestra, and that is likely only achieved with the use of the recorded string quartets. There are a total of eight violins and four each of violas and cellos. If all played live their harmonics would overlap constructively and destructively, with notes across instruments a few cents off, and create closer to the “hum” we hear in string orchestras. Recorded, their individual quartet-ness is retained.

These two works by Boulez and Reich treat the electronics as a filter or echo or prism of the acoustic instruments that they accompany and are accompanied by. Prokofiev’s Concerto for Turntables & Orchestra (2006) does the same. That approach is of a different quality than the one I am taking with the current suite. Though the contrast in timbre is important in all of them, I’m trying to treat the electronics as an instrument in itself as opposed to an altering and enhancing lens of those surrounding it.

Updated 16 Mar 2022

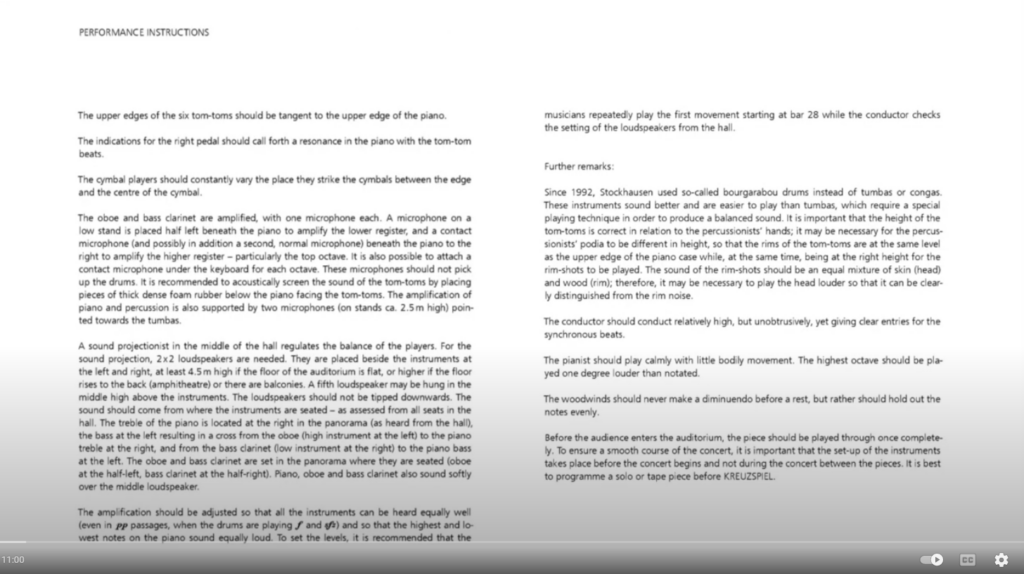

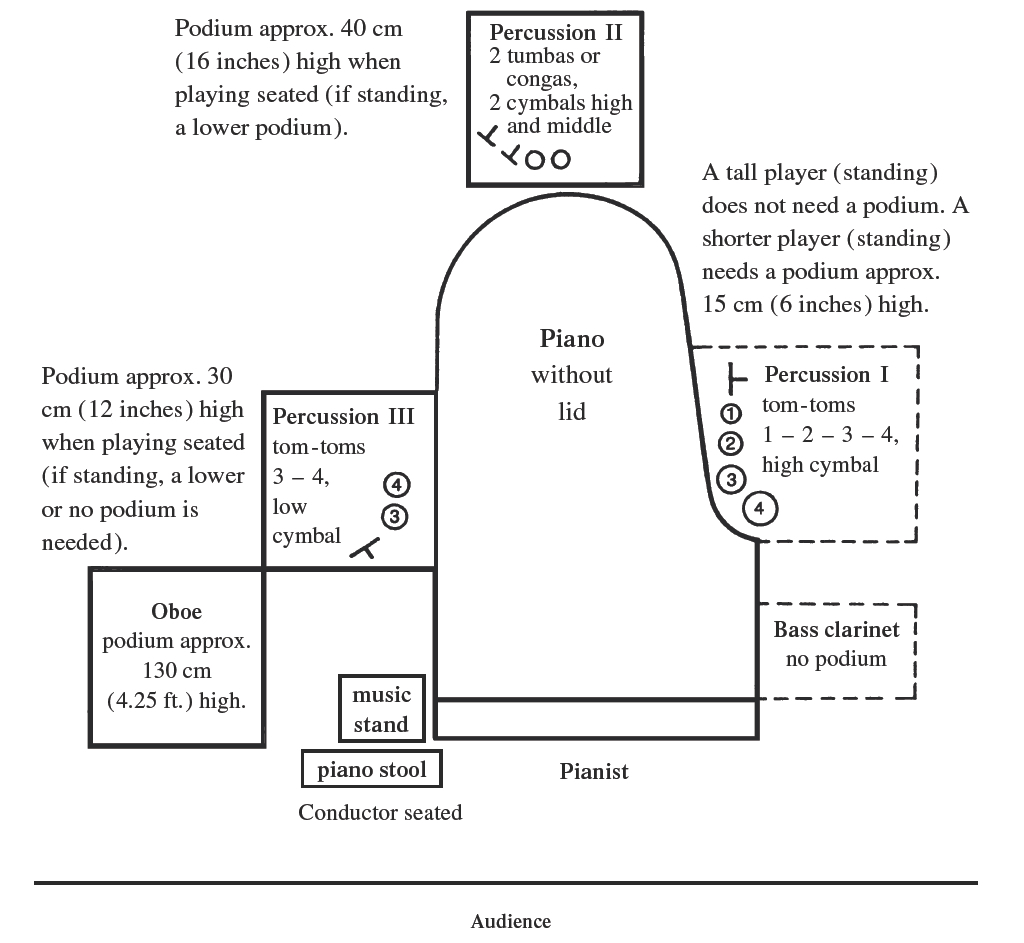

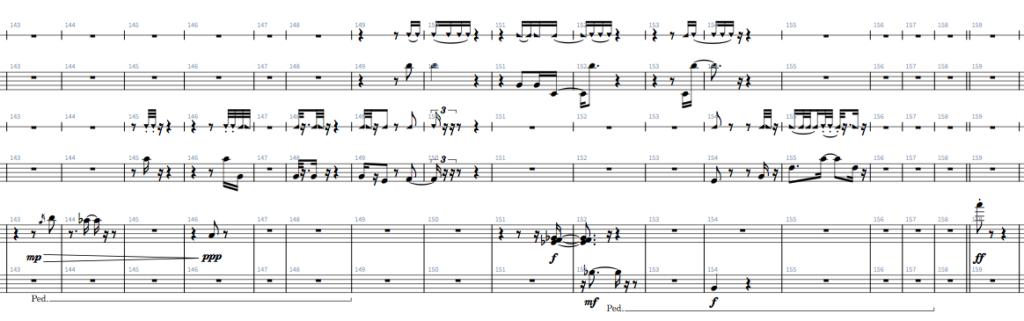

Another crazy-making set of performance instructions are from Stockhausen’s Kreuzspiel. I was reading about, in Modern Music and After by Paul Griffiths, how it was influenced-by the early total serialists and needed to listen in order to get a sense of what he was after (this text and all diagrams from the score are available here on the Stockhausen website). These remind me of the special purpose notation used for dance and movement. See Dance notation on Wikipedia for a terse overview, or get Daniels and Bright The World’s Writing Systems for a more complete examination in section 73 “Movement Notation Systems” written by Brenda Farnell. Turntablism notation very much exists in a similar spectrum, and hopefully it will eventually make it into that book.