First part here. Second part here.

32:56

Discussing Lemma Epigram Icon.

Taking the linear flow and breaking them up into distinct layers of gestural quanta.

–Ferneyhough

Does he mean something similar to distributing the melody across instruments/sections? Maybe more involved.

No overriding system which can be utilized in order to predict which of these elements will come next in the cycle, which of the element will be used to map out others… all occur rapidly.

–Ferneyhough

My shorthand for Ferneyhough is “process composition”, but this suggests a different approach. Process/formalist but with the freedom of improvisation (?). It reminds me of another quote from him–that I’d read while starting my symphony but absolutely cannot source now–about how he started Lemma:

The piece has to start with some material, but it could have started with others; I simply wrote down a set of notes without thinking about them at all, and said, I will work with these. That’s how the piece begins.

–Ferneyhough?

Inconjunctions for 20 instrumentalists, 2014 (~19:12)

- Score – £96.00

- Ferneyhough – Inconjunctions Full Score EP72630 – Editions Peters publishes the work but this site has a pdf of the full score. Expect it to go away.

- Brian Ferneyhough – Inconjunctions (premiered yesterday) (20 Oct 2014) – short but insightful Reddit post from a bassist, @paulcannonbass, who performed at its premiere (!!!)

After two listens: Sections with different groups of instruments and textures, where some instruments and aspects bleed into the next section (gestural quanta?). Range of emotions. This type of piece, or at least the concept since I had never heard it before, influenced an occupying army.

His music has a relationship to Renaissance music (as did Webern) in order to create new musical language. References secunda pratica which describes the modern style of the 1600s that superseded Stile antico, early Baroque such as Paletrina. In his early 20s he was immersed in music of the 1500s. Makes a nod towards historically informed performance [ed. though flawed].

41:23

References the Venetian School of music which often used polychoral/antiphonal choirs/cori spezzati. Eventually spread throughout Europe.

Praises Spem in Alium (1570) by Tallis, 40-part Renaissance motet, and then goes on to discuss his 1975 cantata Transit (~43:39). Spem in Alium was written for 8, 5-part choirs.

Process is itself a thing.

–Ferneyhough

- 3-page performance notes for Transit from Editions Peters (1972-1975)

- Only recorded on vinyl [ Discogs ] in 1977, performed by the London Sinfonietta, Elgar Howarth conducting.

45:32

He is disinterested in contemporary English music (I hear ya, brother).

Finds the Pierre Boulez letters to John Cage “interesting”. Praises Boulez’s work and criticizes another (can’t hear who, at times his video stream is choppy). Later, he declares Stockhausen better than Boulez. I can’t fathom that; but my experience with both are limited. I’ve read around half of Boulez’s collection of essays, Orientations, and listened to several of his pieces that he references and so have a deeper exposure to him. But Stockhausen, though important and groundbreaking, doesn’t move me.

“5 most important composers to me”

- Thomas Tallis

- Claudio Monteverdi

- Jean Sibelius (symphonies)

- Edgar Varese (antidote to Benjamin Brittain and “all types of hi nonny no-type music”)

What’s important to him and not who’s great.

50:48

Stockhausen > Boulez (?!) but he can’t say whether either of them is a “great” composer. “Stockhausen had a tremendous grasp on the inventiveness of form.”

“French music doesn’t have la grande ligne.”

But whatever the form the composer chooses to adopt, there is always one great desideratum: The form must have what in my student days we used to call la grande ligne (the long line). It is difficult adequately to explain the meaning of that phrase to the layman. To be properly understood in relation to a piece of music, it must be felt. In mere words, it simply means that every good piece of music must give us a sense of flow—a sense of continuity from first note to last. Every elementary music student knows the principle, but to put it into practice has challenged the greatest minds in music! A great symphony is a man-made Mississippi down which we irresistibly flow from the instant of our leave taking to a long foreseen destination. Music must always flow, for that is part of its very essence, but the creation of that continuity and flow—that long line—constitutes the be-all and end-all of every composer’s existence.

Aaron Copland from “What to Listen For in Music”, quoted at La Grande Ligne — Excerpt from Copland’s “What To Listen For In Music”, the phrase is attributed elsewhere to Nadia Boulanger

Regarding contemporary composers other than Boulez:

I liked early Birtwhisle because I found he’s a profoundly nasty composer, and that’s something we need in music.

–Ferneyhough

(Birtwistle’s Panic: Postmodern. The soloist can, at the end of phrases, dissolve into the ensemble as it takes over, seamlessly [a personal style]. At times completely distinct from the ensemble but then working together. Saxophone’s timbre stands out clearly against the woodwinds and brass. If the drum kit weren’t there, I wouldn’t associate it so strongly with free jazz. Beautiful last few minutes.)

55:06

Andreyev: Boulez has one technique, yours (Ferneyhough’s) varies.

Ferneyhough: I continue [to evolve] from piece to piece. Sounds you created previously inform the next; listen in succession but not all are successful.

–imprecisely quoted

In the 70s/80s, music was an amazing communicative medium because it showed us all aspects of what being might be: transitive, intransitive, transparent, opaque, rhetorical, poetic. And all of these different aspects can be transformed into one another.

–Ferneyhough

59:30

Bring “historical thinking” into music. That approach was not there in 70s/80s.

~1:02:00

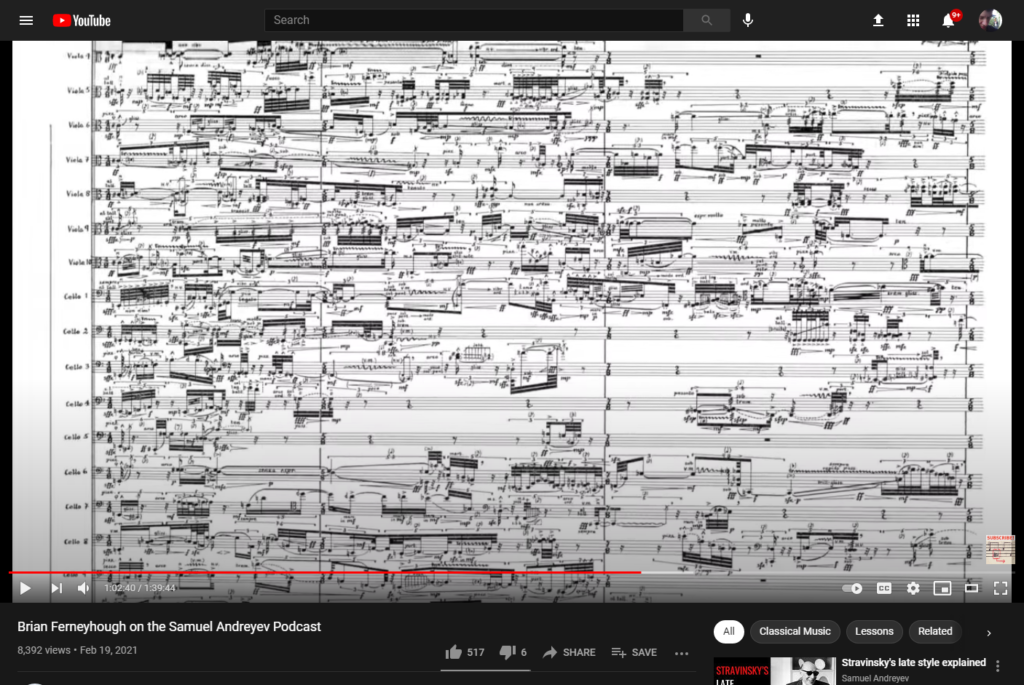

La terre est un homme (1976-1979), 42 pages, 12:58

The means to listen to the piece is in the piece itself.

–Ferneyhough

…

Does material fulfill its form or is form external to material?

This piece, on one listening, is completely impenetrable. (The above is the 2011, definitive-and-only recording.) From a painting by Chilean surrealist Roberto Matta.

See the entry at The Art Institute of Chicago for an excellent preproduction that can been zoomed in to see the oil-that-looks-like-watercolor technique.

- Score – $67.00

- Ferneyhough – La terre est un homme, Full Score EP7225 – Editions Peters publishes the work but this site has a pdf of the full score. Expect it to go away.

- Ferneyhough: La Terre Est Un Homme / Plötzlichkeit review – massive and mesmerising (The Guardian, 9 Mar 2018)

The first performance of Brian Ferneyhough’s La Terre Est Un Homme in Glasgow in 1979 is remembered as a disaster; sabotaged, so the story goes, by the orchestra’s hostility to a score of such challenging density.

–Andrew Clements, The Guardian

…

[T]he BBC Symphony Orchestra’s revival of La Terre Est Un Homme in 2011 went a long way to redressing the balance. A recording of that outstanding performance, conducted with astonishing lucidity by Martyn Brabbins.

Describes Ploetzlichkeit (which is on the same recording as La terre) as self contained units with non sequiturs (not to be a broken record, but this is the entire conceit of I am now) and a memoryless structure. The difficulty is how to keep it engaging.

1:08:00

- Ploetzlichkeit (Suddenness), ~22:30

- Ferneyhough – Ploetzlichkeit, Full Score EP7884 – Editions Peters publishes the work but this site has a pdf of the full score. Expect it to go away.

Regarding Ploetzlichkeit: “[The] speed [with which] I was composing… I should have taken more risks with the density of the material.”

Speaks of using writing with process (again) and yet struggling against that process. As an example, he describes how the structure may dictate 6 measures, but a different length may be more appropriate. (The art is the balance between those decisions: an encompassing structure that suffuses the listener, with specific lyric/harmonic phrases that captures their “active” attention).

“Beginnings and ends are important.” (yes)

1:13:00

More on Ploetzlichkeit.